Industrial Policy for Economic Transformation in Uganda

This blog post is a reproduction of the Executive Summary of Reality Check 12: industrial Policy for Economic Transformation in Uganda. The full PDF version of the Executive Summary is downloadable here.

Introduction

Effective industrial policy has been at the core of virtually every economic transformation success story around the world. After three decades of neoliberal economic management, and faced with stalled transformation, the Government of Uganda (GoU) now demonstrates a renewed interest and con dence in proactive industrial policy. While its efforts to date have lacked focus and depth, there is now a clear sense of reflection on the next phase of industrialisation strategies: a National Industrial Policy has been drafted, and an Industrialisation Masterplan commissioned.

The prospect of industrial policy success hangs in the balance: it can kickstart the deeper transformation so sorely needed to provide decent jobs and incomes to Uganda’s bulging youth population, but can just as easily become an extractive tool for patronage politics that stifles economic progress.

This in-depth study aims to help shape the next phase of industrial policy in Uganda by injecting rigorous analysis and fresh ideas into the discourse. It brings together valuable lessons from Uganda’s own past and from the rich global literature on the politics, delivery, and content of industrial policy.

Photo credit: Martin Jjumba

Photo credit: Martin Jjumba

Analytical Framework

Economic transformation – the movement of labour and other resources from low- to high-productivity economic activities – is necessary for sustained growth in output, decent jobs, incomes, and social development. Economic transformation relies on the acquisition of new productive capabilities in higher value-added economic activities. Traditionally, there have been two phases of structural change driving across-sector economic transformation: from agriculture to manufacturing and then to services. Today, certain services as well as high-value agricultural products have become key drivers of economic transformation even for early-stage developing countries. Recent empirical evidence demonstrates that manufacturing is still a key engine for economic transformation in both developing and developed economies. Ultimately, what matters for economic transformation is moving towards higher-value-added activities with spill-overs and linkages that are able to absorb a large portion of an economy’s productive resources, especially labour.

Industrial policy is broadly understood to refer to a range of government interventions aimed at altering productive structures toward higher-productivity sectors and activities by changing the incentives, constraints, and resources available to economic actors. There are many well-documented cases of industrial policy success and failure, but virtually no cases of economic transformation success without effective industrial policy. Success cases exist on every continent, and many governments of the most advanced economies are still employing industrial policy in order to maintain their competitiveness. There are also compelling theoretical arguments for industrial policy, particularly based on the notion of market failure. This is the idea that, if left alone, competitive markets will not yield the best result for society. The most important market failures that would justify government intervention arise because of the presence of: i) economies of scale, ii) externalities, or iii) market imperfections. Beyond fixing market failures, industrial policy can actively provide a vision that helps markets shift resources into high-value-added activities in the long-run, and foster firm- and system-level capability development. While not all efforts of industrial policy have been successful, the evidence suggests that under the right circumstances, it has been instrumental to economic transformation episodes.

The success or failure of industrial policy is influenced by a range of factors, the most profound of which is the political economy. The political forces shaping industrial policy outcomes in a given country are driven by its underlying political settlement – the balance of power within and beyond the ruling coalition. Industrial policy has the best chance of success when cohesive coalitions and conducive power dynamics exist between the political elite, the state bureaucracy, and the capitalists.

Photo credit: Ed Ram

Photo credit: Ed Ram

Second, industrial policy effectiveness is dependent on the ability to galvanise and organise key interests around a shared transformation agenda. In successful industrialisers, this has generally been achieved through a powerful central coordination body that is technically and financially empowered and politically insulated from particularistic interests. Effective sector development and specialised agencies have also played a key role in many cases.

Third, it is driven by the choice of economic sectors, actors, and activities to be promoted by industrial policy. Successful industrialisers have tended to concentrate scarce resources on a narrow set of target industrial sectors or activities. A growing literature proposes various methods for evidence-based sector- or activity-selection for industrial policy.

Finally, industrial policy outcomes are shaped by the choice (and thus suitability) of the policy instrument mix, and how well this is adapted based on success, failure, and changing contextual factors. Countries with successful economic transformation outcomes have deployed a rich ‘toolbox’ of industrial policy instruments to shift the incentives and capabilities of economic actors towards higher-value-added activities. Crucial to the success of these instruments is the combination of supporting and disciplining the private sector – including domestic and foreign investors – in a way that compels them to shift resources away from short-term rent seeking and towards continuous investment in new productive capabilities. This has required ongoing public sector capabilities to learn from and adapt policies and incentives.

Photo Credit: Ed Ram

Photo Credit: Ed Ram

History

Important lessons can be drawn from Uganda’s history of political economy, industrial policy, and economic transformation. Uganda’s political settlement was highly volatile from independence through to the ascent to power of the National Resistance Army in 1986. After short-lived industrial policy efforts in the 1960s, Uganda’s economic policy was disrupted by political instability and war for two decades. Some modest but interrupted economic transformation took place in this period.

From 1986 to the mid 2000s, the National Resistance Movement’s (NRM) largely stable ruling coalition was able to usher in a consolidation of national security together with macroeconomic stability. This unlocked Uganda’s first episode of sustained high GDP growth, which was coupled with promising signs of early economic transformation, including strong export growth and diversification. This growth was driven by post-conflict reconstruction, large donor funding inflows, investment by previously exiled industrialists encouraged to return by the NRM, and the global commodity boom of the 2000s.

However, progress against each economic transformation metric eventually stalled. First, there was an accelerating shift of labour from agriculture into manufacturing and services, which however halted abruptly in the mid 2000s. Second, Uganda’s export basket diversified significantly from 1995 until the late 2000s. Third, manufacturing growth also seems to have stalled, both as a proportion of total output and in terms of absolute export growth. Moreover, the growth witnessed in this period was accompanied by increasing inequality and underemployment as well as stagnant agricultural productivity, and employment. In the 2010s, even GDP per capita growth has oscillated around a much lower average than that seen in the 1990s and 2000s.

The shallow and then stalled economic transformation of the past decades has translated into “jobless” growth as well as stagnating incomes for most people. Low-productivity sectors such as agriculture and traditional sectors are still much larger than higher-productivity sectors including manufacturing. Roughly 8 million working people are stuck in a poverty trap of low-productivity subsistence farming, while underemployment and vulnerable employment in the informal sector are widespread, occupying the majority of the labour force. Unemployment in Kampala is above 20% (and above 9% nationwide) (Kiranda et al., 2017; Walter, 2019). The absolute number of people living below the national poverty line has grown from 7.7 million in 2009 to 9.1 million in 2018 (The World Factbook, 2020).

Several stakeholders attribute these economic transformation shortfalls to an economic liberalisation agenda that went too far. The policy rubric of the last three decades has largely followed the neoliberal Washington Consensus prescriptions to the letter, with deep liberalisation, privatisation, and deregulation occurring through several reform programmes financed by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. That policy framework precluded any meaningful industrial policy.

Since the 2000s, active industrial policy is clearly coming into favour among the political elite. This is visible through recent policies and strategies (notably Vision 2040, the 2008 National Industrial Policy, and the 2015 and 2020 National Development Plans) that name industrialisation as a principal priority and explicitly recognise the central role of the state in driving economic transformation. It is also evidenced by an increasing focus on power and transport infrastructure as well as the emerging targeted industrial policy efforts discussed below.

This policy shift towards greater state involvement is at least in part a response to the realisation that the private sector, left to its own devices, is unlikely to make long-term coordinated investments in the technology and capabilities needed for new higher-value-added economic activities. It can also be argued that the NRM leadership, particularly the president, has in fact been a believer in state-driven industrialisation all along, and that the shift of western development financiers away from their earlier staunch neoliberal views as well as the new availability of Chinese development finance now allow the president to be more assertive in that long-held conviction.

Photo credit: Martin Jjumba

Photo credit: Martin Jjumba

Present

Recent nascent industrial policy efforts have begun to move beyond generic infrastructure provision and started targeting specific sectors and activities, but this targeting has thus far been too broad, inconsistent, and poorly evidenced to be effective. Import substitution is currently being promoted without sufficient attention to the longer-term goals of reaching international competitiveness and boosting exports. Similarly, the focus on value addition and agricultural linkages could be complemented with other efforts, for example, towards becoming the regional supplier of strategic inputs including iron and steel and simple manufacturing products such as food and wood products. Further, each planning document lists different priority sectors, the discussion of policy instruments and delivery channels is convoluted, and the evidence base for policy decisions is unclear.

Further, Uganda has only just begun to tap into the industrial policy “toolbox” of instruments that successful industrialisers have employed in transforming their economies, and its efforts to-date have lacked coherence and focus. Crucially, it has not made sufficient use of the combination of both supporting and disciplining the private sector, which has been central to industrial policy effectiveness elsewhere.

The emerging industrial policy tools in use are clustered around the following areas:

- Electricity infrastructure development through large new hydroelectric power stations, coupled with cross-subsidisation to allow low power tariffs for large industries;

- Transport infrastructure development, particularly through expanding the paved road network, as well as early-stage or planned efforts to upgrade the port, airport, and railway infrastructure;

- Targeted tax holidays, exemptions, and rebates for a range of large investors, notably those located in industrial parks and free zones, mostly negotiated on a case-by-case basis;

- Export levies on a few selected raw materials (notably fish, hides and skins, timber, and iron ore), with, at best, patchy success in stimulating domestic value addition;

- Free or subsidised land in a handful of now active industrial parks, but also provided to individual selected firms outside parks;

- Protective import tariffs on a range of value-added products, though often targeted at already well-established industries rather than new activities and sectors;

- Public investment and subsidised credit into pioneer firms through the recently reconstituted Uganda Development Bank and Uganda Development Corporation, who have however received little government capital to-date; and

- The promotion of local content through ad-hoc efforts under the Buy Uganda Build Uganda policy, two Acts targeting the oil and gas sector, and prospectively through the National Local Content Bill, 2019, passed in parliament in June 2020.

Photo credit: Martin Jjumba

Photo credit: Martin Jjumba

Future

With one of the fastest-growing working age populations in the world and a median age of 16 years, the magnitude of Uganda’s employment challenge, and the political discontent it risks causing are set to grow exponentially in the coming decades. Faced with a bulging, urbanising and increasingly educated youth population that has no living memory of the painful liberation struggle that brought the ruling party to power in 1986, the political legitimacy of Uganda’s leadership will increasingly depend not only on peace and stability, but also on the promise of decent work and incomes for all. The latter will require the creation of decent jobs at scale through growth in labour-intensive higher-value-added activities with continuous upgrading.

Even though Uganda faces several challenges as a small, landlocked country, it has untapped opportunities to reinvigorate economic transformation. To realise this objective, the country’s natural resources (including its agricultural potential), abundant labour force, and strategic regional location will need to be leveraged as part of a long-term economic transformation strategy. Uganda has the potential to leverage both its imminent demographic dividend (a low dependency ratio driven by a youth bulge entering the workforce) and its strategic geographic location to become a production and logistics hub serving its own growing consumer population as well as neighbouring economies (AEC, 2019). Stability in South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo will, however, be a strong pre-requisite. Uganda may also produce more high-value goods and services for growing global consumer markets, including those in Asia.

Any stakeholder genuinely interested in effectively formulating and implementing industrial policy in Uganda – including the President – has an uphill political struggle to fight, but there is cause for hope. Efforts to promote productivity growth are constrained by the short-termist and extractive pressures of patronage politics and vested interests that have gained sway in a fragmenting political settlement. But, despite a generally weak and politicised state bureaucracy, the political elite has been able to use the little “disposable” political capital it possesses to carve out “pockets of efficiency” in certain periods. Examples include the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development (MoFPED), the Dairy Development Authority (DDA) and the National Water and Sewerage Corporation (NWSC). However, in general, Uganda’s bureaucracy has struggled to maintain the insulation from special interests that is crucial for industrial policy to work.

Photo credit: Martin Jjumba

Photo credit: Martin Jjumba

Going forward, industrial policy effectiveness will require:

- The creation and protection of one or more pockets of e ciency within the government dedicated to driving, coordinating, and monitoring industrial policy formulation and delivery;

- A carefully focused, prioritised, and risk-adjusted portfolio of target sectors and activities;

- A smarter and more comprehensive use of industrial policy instruments that:

- Provides support and protection exclusively to these priority areas;

- Deepens that support to meaningfully enable the development of new productive capabilities;

- Couples that support with requirements, performance pressure, and culling of losers to shift the private sector’s incentives; and

- Takes a more regional approach to industrial development.

First, if pockets of efficiency that drive economic transformation are to be created and maintained, industrial policy must become a top priority for the political elite and its supporters, and innovative delivery channels that navigate the prevalent political economy conditions must be devised.

Given the scarcity of political, financial and technical capital available for industrial policy in Uganda, its champions must find and protect narrow spaces for progress. We explore three ways to do so:

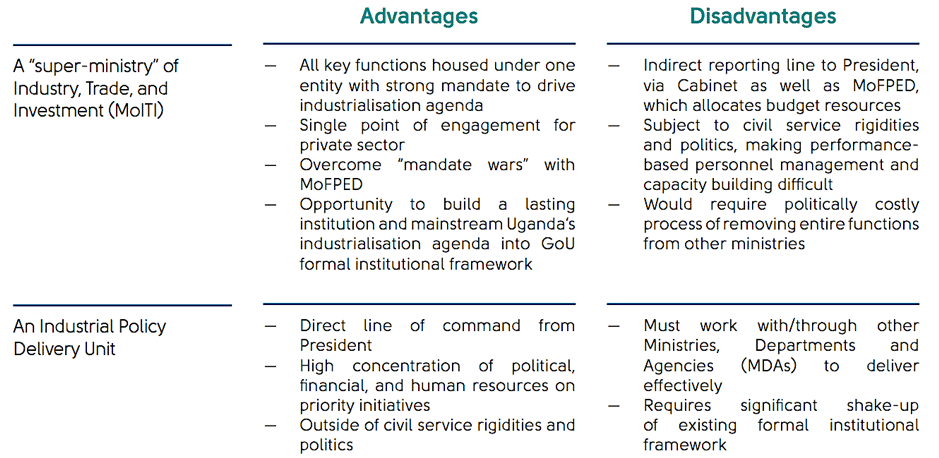

Source: Authors

Source: Authors

Second, Uganda needs a carefully focused, prioritised, and risk-adjusted industrial policy, with clearly defined principles for identifying the most suitable economic sectors and activities to promote.

These principles include:

- Applying a combination of selection tools to identify a set of priority industrial sectors and activities that is coherent and consistent across all government policies and strategies;

- Developing a long-term vision, both economy-wide and within priority sectors, and a phased and iterative approach that builds on previous successes and learns from failures;

- Taking into account contextual factors and longer-term risks and opportunities;

- Applying a combination of selection tools;

- Using both quantitative and qualitative measures to score potential target activities according to both strategic value and feasibility; and

- Selecting a mix of lower-risk and higher-risk priority industrial sectors and activities.

Finally, with reference to success cases from around the world, we explore several ways in which the Government of Uganda could make use of industrial policy instruments to achieve genuine economic transformation. These can be grouped under four headings:

Source: Authors

Feature Image: Martin Jjumba

Max Walter is Co-founder and Executive Director of the Centre for Development Alternatives. He has led CDA research and strategy work on industrial policy, agricultural value chains, SMEs, entrepreneurship, financial sector development, energy, skills development, and labour markets. Previously, he worked in D.R. Congo as a programme manager and technical adviser on ELAN RDC, one of the largest market systems development programmes worldwide. He has also worked as an independent economic transformation expert for a range of international development consultancies. He holds an MSc in Development Management from the London School of Economics and a BA in Philosophy, Politics and Economics from the University of York.